Southwest Finland is taking a leaf from nature’s book when it comes to building climate change resilience.

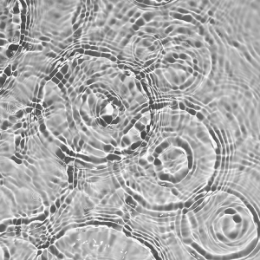

Southwest Finland has a water drainage problem, and it is being exacerbated by climate change. Contrary to marshy and lake-abundant interior and northern reaches of the nation, this region lacks natural water retention bodies, making it more prone to flooding and stormwater run-off during the increasingly mild and rainy winter seasons. Couple this with longer and more severe droughts in spring and summer, and you have a cocktail of climate challenges in natural, agricultural, and urban environments.

Farmers in Southwest Finland, known locally as the Varsinais-Suomi region, are among the most affected by the changing climate. Prolonged droughts during growing periods and increased rain in the winter do not cancel each other out, but rather they combine to amplify hazards such as soil erosion and nutrient leaching, which in turn feed the eutrophication – an overabundance of nutrients – of natural bodies of water like the vulnerable Archipelago Sea, part of the Baltic Sea. These impacts are forcing local farmers to overhaul the way they work the land.

The Nation’s Granary

Martti Hyssälä is one of those farmers. Now at the helm of his family farm in the municipality of Lieto, he is still learning to adapt to a climate that is increasingly alien to that of his childhood. Stood in one of his wheat fields on a bright sunny day, he tells REVOLVE that it rained only twice in the local area in June 2023. “What I remember from my youth, back in the 1980s and 1990s, there used to be a constant rain at least, but nowadays, in the last six or seven years, the dry season has been longer and longer and with occasional rain only […] The dry seasons are affecting us a lot more than they used to in my youth.”

To bolster his farmland against the threat of soil erosion, Hyssälä has turned to the use of winter crops, which help to bind the soil, lock in nutrients and create subterranean channels to boost irrigation and root growth during the spring. He is also reducing his use of fertilizers and pesticides. “I am increasing the winter wheat and rye, so that the roots in the summertime will be deeper in the soil. I’m also trying to get more carbon into the fields, so I’m switching my fields of wheat with grassland and switching those grassland (fields) with my cousin, and I also get manure from the dairy cattle,” he says.

Around 26% of the land in Southwest Finland is used for agricultural purposes, according to the Natural Resources Institute Finland. As the nation’s breadbasket, climate solutions in the region are of national importance. Marita Rasimus – a third-generation farmer also in Lieto – has also noticed more severe spring droughts. She, too, has changed the kind of crops she sows.

“Compared to what was cultivated during my father’s time, there have been quite significant changes in many ways. Of course, from a climatic perspective, it is important to consider the types of crops being cultivated and there have been specific changes made at the variety level to adapt to these changes,” she says.

“The worst challenge in this region is the springtime dryness, which has necessitated changes in cultivation methods. Perhaps the most significant change has been the shift to no-till farming,” she continues, adding that she has also installed a settling pond on the farm to irrigate crops during dry periods.

How not to lose a plot

The effects of climate change are not confined to the rural areas of the region. Tuula Hannula is a member of the 4H gardening association and has cultivated a vegetable plot on the outskirts of Turku for 10 years. In that time, she has seen a lot of changes.

“I don’t know if it’s climate change or if the drainage area has increased – but a lot of stormwater comes here,” she says during an interview at her allotment, one of many acres of land leased out by Turku to its green-fingered residents. The drainage system of the vegetable plot area is characterized by man-made rain ditches, but this often proves to be insufficient.

“So, when there is heavy rain, this stormwater, it flows mostly through the ditches. The drains are not functioning properly, the water flows across the road and the fields are left underwater,” Hannula says. Like the farmers, she has also noticed the indicators of rising temperatures, including new species of butterflies buzzing around the plot.

A moment for watersheds

Aside from the economic and societal damage incurred by increased winter flooding and soil erosion in the region, one of the main reasons that finding climate solutions is to ensure the protection of the Archipelago Sea. Characterized by thousands upon thousands of islands and islets, shallow waters and unique biospheres, the Archipelago Sea is highly vulnerable to eutrophication, which is exaggerated by increased rainfall and stormwater runoff.

People like contributing to good things if it is easy

Piia Leskinen, Turku University of Applied Sciences

Water flows are set to increase during the winter period in Southwest Finland, with more extreme rainfall and less permanent snowfall and ice, warns Piia Leskinen, Leader of Research in Water Engineering at the Turku University of Applied Sciences. Leskinen is contributing her expertise to the RESIST Project, an initiative co-funded by the EU that is supporting Southwest Finland in the testing of climate resilience measures with a heavy emphasis on nature-based solutions (NBS).

“Climate change is seen as a major threat to the Archipelago Sea nutrient situation, because the high flows and precipitation during wintertime is expected to increase. And if we have less snow cover and it’s raining on bare land, and the vegetation is not binding the nutrients efficiently because it is not the growing period, then this will significantly increase the nutrient flows in the Archipelago Sea,” she tells REVOLVE in an interview.

Rain gardens

Nature-based solutions come in many shapes and sizes depending on the challenge at hand. Southwest Finland, a RESIST pilot region, is in need transformative solutions but they also need to be accessible, affordable and attractive for local municipalities and private landowners, Leskinen says.

“We don’t have space for very large solutions that would handle the flooding or surface waters of a large drainage basin. So, we need to have a lot of small-scale solutions and that means that they need to be very cheap, because whether it’s farmers of private land in the urban areas, they don’t want to spend major sums of money on investments. The maintenance must be sort of simple because nobody will be maintaining them on a regular basis.”

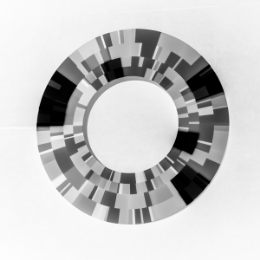

An NBS that works particularly well in tackling stormwater run-off and flooding in Turku and Southwest Finland is the humble rain garden, a tried and test measure that encourage the reabsorption of rainwater into the soil. Rain gardens can be planted with perennial plants that not only encourage biodiversity but also lift the aesthetics of their surroundings.

The benefits of rain gardens are well established, but the challenge in implementing them wider in Southwest Finland often boils down to a lack of awareness among both public and private stakeholders, Leskinen says. To make them more accessible, RESIST will work with local garden shops to produce a catalogue of rain gardens directed at private citizens, businesses and landowners that will be much like browsing products online.

“One of the main problems as to why there are so few NBS in private properties is the uncertainty related to costs. If you have a stormwater cassette that’s underground, then it’s easy to define the costs, but with NBS then it’s not.”

The solutions being tested in Southwest Finland and Turku, a city that has won numerous international awards for its leadership on climate change, will be analyzed, quantified and transferred to other regions that are less experienced in climate adaptation as part of RESIST. The project brings together 12 regions with different socio-economic profiles and levels of climate preparedness.

Southwest Finland is among the four beacon regions, alongside Catalonia, in Spain, Central Portugal and Central Denmark. It is paired with Normandy in France and Eastern Macedonia in Greece, which face similar climate threats when it comes to sustainable water management and flooding. The RESIST Project is working with local authorities to harness science and technology in a bid to tackle climate change impacts on five fronts: floods, droughts, heatwaves, wildfires, and soil erosion.

NBS and digital twin technology sit at the core of the project, which is responding to the need of European regions to prepare for the effects of a changing climate in harmony with nature.