Water governance is turning to new technologies and nature for management solutions.

The re-emergence of the medieval Sant Romà de Sau Church from the shrinking Sau reservoir in Catalonia has become a symbol of the Spanish region’s water crisis. The bell tower of the Romanesque church has served as an indicator of water levels since the area was submerged in 1962.

When the reservoir is full, only the tip of the tower protrudes from the surface of the water. Periods of drought not only reveal the crumbling building in its entirety but also our need to adapt our water management systems in time for what will soon become – or perhaps what has already become – the “new normal.”

As of 2 June 2023, amid prolonged and severe drought conditions in Catalonia and the wider Iberian Peninsula, the Sau reservoir was at around 14% of its capacity – a decrease accelerated by local authorities emptying the water into a fuller reservoir further downstream on the Ter River. Average reservoir capacity levels in Catalonia hovered at 25% as of the same date, according to the Catalan Water Agency (ACA).

Periods of drought are commonplace in the Mediterranean, but science has shown that climate change will make them more frequent and severe. The region is warming 20% faster than the global average and its rainfall in spring and summer is expected to decrease by around 30% by 2080.

To prepare for this scenario, we must draw on all the scientific knowledge and evidence available, re-evaluate our relentless demand for water and further study how nature-based solutions (NBS) can help the region prepare for the evolving climate crisis, according to Annelies Broekman, water management expert and researcher at the public research center CREAF.

Climate Resilient Decision-Making

Catalonia has good quality water planning for ‘normal times’ and periods of drought in line with the principles and concepts in the European Water Framework Directive. But when it comes to addressing the water crisis and adapting strategies to meet the pressures of climate change, there are several factors that threaten to hinder the timely application of necessary measures, Broekman tells REVOLVE in an exclusive interview.

These factors include overly rigid policy-making structures, a lack of harmony between decision-making bodies and conflicting interests between industries.

“If you have agricultural policy pushing for more irrigated crops and on the other hand you have a water management plan saying ‘I don’t know how I’m going to save this river’ then you have a clash. And they leave citizens to fight it out. It should not be a struggle between the agricultural sector and environmentalists. It should be in a policy harmonization idea of how we manage this territory,” Broekman says.

A swift and holistic response to the water crisis in Catalonia becomes further complicated when decisionmaking is delegated and split across territories and municipalities that often lack the powers and coordination needed to address water management issues.

The overarching nature of the water crisis calls for adaptive, cross-sectoral approaches toward co-designed solutions that acknowledge all relevant actors and factors within a territory, from people and socio-economic considerations to the private sector.

From theory to practice

“Only by implementing theoretical frameworks can we see if it works or not,” Broekman tells REVOLVE. That is what a CREAF team led by Broekman is doing in Maresme County, an area on the Catalan coast north of Barcelona that is facing climate crisis-linked events from droughts, floods, heatwaves and wildfires to coastal erosion and rising sea levels.

The CREAF team started working with the Consell Comarcal del Maresme – a supra-municipal governance body – because they decided to “take the climate emergency seriously,” Broekman explains. The Consell Comarcal represents the 30 municipalities in the county and works to support those local entities and ensure that policies are coordinated beyond short-term electoral objectives. The municipalities agreed on the pressing need to work on climate change adaptation and unanimously approved a climate emergency statement in March 2021.

The Consell Comarcal obtained a strategy for climate change adaptation drawn up by experts in the field but hit hurdles when it came to translating it into effective policies, as tends to happen with smaller governance bodies. “It is a big document, very well done, but they don’t know what to do with it because it says that they need to change everything,” says Broekman.

This is where the CREAF team came in. The first step it took to support the Consell Comarcal del Maresme was to engage scientists with the creation of a Scientific Committee composed of 38 experts with knowledge and experience in the geographical area. “Too much of the complexity of climate change impacts is lost in decision-making because too often policies are based on intuitions,” Broekman adds. “We need knowledge, and we need to learn from each other.”

The outcome of the committee’s first assessment was presented to the municipalities in a second phase that provided local policymakers space to contribute to the final plan. The final Strategy for the Energy Transition and Climate Adaptation of Maresme County by 2030 was presented in January 2023 and approved by the 30 municipalities in the county. The document integrates scientific knowledge and analysis with an on-the-ground understanding of the municipalities, matching it up with existing policies and integrating synergies with active plans and programs.

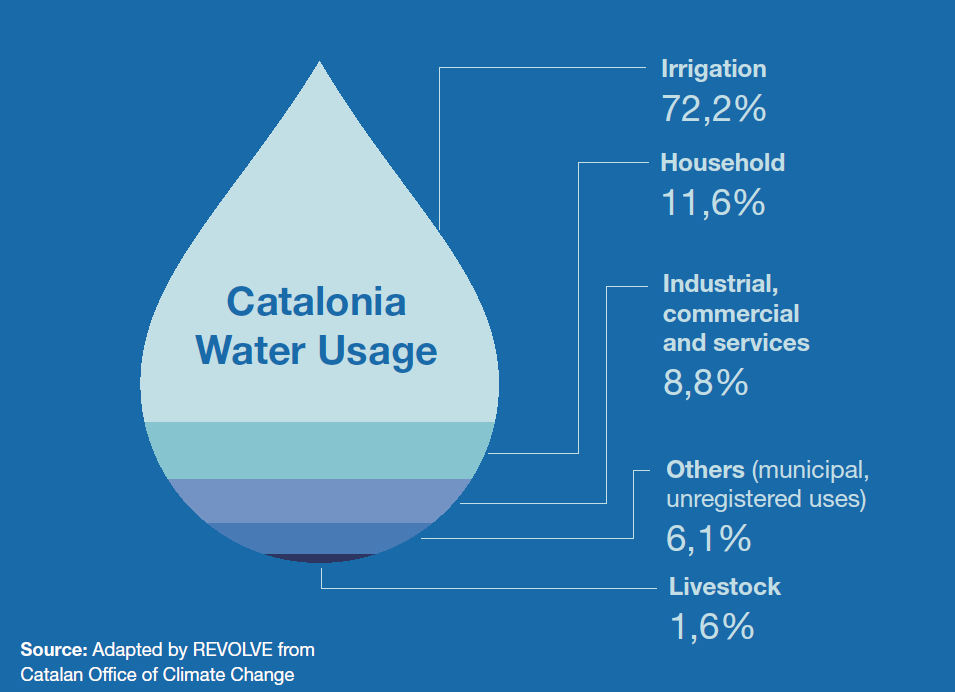

Average water capacity levels in Catalan reservoirs stood at less than 25% in spring 2023.

Source: Catalan Water Agency (ACA)

Water management holds a prominent position in the strategy, forming “the backbone of the adaptation of the county.” The strategy not only aims to foster a more comprehensive management of the entire water cycle and establish a participatory model, but it also highlights the need to view the water cycle as a hydro-social cycle.

It integrates a crucial point not often included in water management plans – the need to reduce total water consumption. “Economic development always overrides environmental constraints, until now, in policies. This needs to change because the basis of all the economic development policies is the stability of the environment. If we lose this stability, businesses will also fall down,” remarks Broekman.

Long-term planning

The Maresme municipalities are now in the position to start implementing this longer-term roadmap and to open governance spaces with other stakeholders like citizens and businesses. CREAF is also putting the initiative on the map by showcasing the experience in Maresme to others. “It would be really cool now to have other people doing the same things and teaching us how it went and how they took it over,” the CREAF researcher explains.

Climate change-related problems seem too big, complex, and far away for smaller municipalities, she adds. “What we are trying to do is to promote municipalities between them and show that problems are shared so they don’t feel alone,” she says.

By sharing the work done in the Maresme area in other forums, regions, and municipalities, or incorporating approved action points from the strategy into projects funded by the European Union (such as Interreg Euro-MED, Horizon Europe, or LIFE), local communities in Maresme and beyond can receive additional funding and technical support.

European financing is a key element for regions and municipalities that normally lack access to funding or technical resources. The European Commission has shifted its focus toward working directly with local authorities to improve climate change adaptation and resilience. For example, two out of the five EU Missions included in the Horizon Europe program focus specifically on regions, cities, and local communities.

The municipality of Blanes – bordering Maresme County to the north – joined one of the EU Missions by participating in the RESIST Project. Josep Lluís Pouy, Head of Civil Protection in the municipality of Blanes, tells REVOLVE in an interview: “Being part of RESIST gives us a technical vision at the research and university levels. In addition, it provides computing resources that are available to create tools and also a window to learn how the work is being done elsewhere. And it also gives us financial resources to have a technician dedicated to this work.”

Blanes is a coastal municipality in the Catalan province of Girona. It is suffering the effects of the severe drought in the region. Among other measures to reduce water consumption, following the Catalan government directives, the municipality decided not to install showers on its beaches. This measure could reduce overall water consumption in a region that receives a high influx of visitors in the summer season. However, as Pouy explains, the most effective tactic is to raise awareness among citizens, especially children.

Like its neighboring municipalities in the Maresme, Blanes suffers from other climate change-related events like heatwaves, wildfires, and floods. The municipality is one of the RESIST Project pilot areas in Catalonia – along with Terrassa – working to improve resilience to multi-hazard challenges linked to climate change. Both municipalities are already working to identify areas and communities at risk from climate change impacts. After this initial assessment, they will start integrating the Argos tool to manage weather-induced hazards.

The tool analyzes data coming from sensors, weather forecasts, and historical records, and sends SMS risk alerts directly to emergency services and even private citizens. “Instead of saying tomorrow it will rain 20mm, we can say be careful because tomorrow it will rain and this industry or this area will be affected,” says Xavi Llort, R&D Manager at HYDS, providers of the Argos service.

Blanes will start testing the Argos tool for flashfloods, but the tool can also be used to identify drought or heatwave risks and alert the governance bodies to act. Nevertheless, “we need to change the paradigm of identifying a risk and finding a solution to mitigate that risk when it happens. We need to identify the risk and change the approach to be more resilient and avoid the emergency,” Pouy adds, in line with the approach being implemented in Maresme county.

Turning to nature

In the short term, the regional Catalan government’s Special Drought Plan for each drainage basin paves the way for a proactive approach to dealing with the challenge the water shortage poses, with clear rules for everyone.

It envisages the use of technology to produce water. That means managing the scarcity of water by producing enough to meet demand through reuse and desalination, for example. While useful in the short term to cope with isolated droughts, such technology-based solutions are not workable in the long term because of their economic, energy, and environmental costs.

And what if the lack of water becomes chronic rather than transient?

The smartest and most immediate solution would be to rein in our insatiable thirst, to curb demand and realize that our socio-economic way of life is unsustainable. This requires a change in mentality that prioritizes the health of bodies of water and natural ecosystems over societal and industrial demands.

Such a change of mentality needs to start today, as does another vital undertaking, that of beginning to meaningfully implement measures to restore, maintain or improve our hydrological systems.

This includes the protection of aquifers and the restoration of natural river courses and ecosystems. Such conservation involves restoring wetlands, rivers and streams, establishing adequate environmental flows, reviving riverside woodland, and making society aware of the fragility of the river environment.

“We have to recover very basic knowledge on biology and geology on how we maintain the rivers’ functioning – rivers as a basin, I mean, all the water bodies interconnecting. This needs to keep functioning and many people don’t understand why,” CREAF researcher Broekman says.

“They say ‘let’s have a desalination plant, let’s overexploit all the resources, well, the ecologists don’t want the fish to die.’ But what I say is if you don’t have the fish the water in the river is poor and you need to treat it and it will be very costly.”

“On top of this you have wildfires, the whole habitat collapses, you have plagues in your agriculture. You are the fish. You need to have the fish in order to have your business. One fish is very valuable if you look at it in this way.”

What’s the difference between drought and water scarcity?

A meteorological drought is a prolonged lack of precipitation, while scarcity (also known as hydrological drought) refers to there not being enough water available for all the different things we use it for.

Water scarcity can be gauged by means of the water exploitation index (WEI), an indicator that reflects the pressure on resources of fresh water and measures annual water consumption as a proportion of the total available.

In 2019, according to the WEI, Cyprus, Malta, Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain experienced the worst seasonal water scarcity conditions in the European Union, which goes to show that we consume too much water for our system to handle even in ‘normal’ times.

Source: CREAF