Communities in Spain spy economic opportunities in wildfire prevention

A charred pine forest runs along one side of the valley on the way to the sleepy village of Descargamaría in the Sierra de Gata. It offers a stark reminder of the perils of the summer months, when local communities in this remote corner of Spain’s Extremadura region brace themselves for wildfires, which are being fanned by climate change and a rural exodus.

Forest blazes like the one that scorched 10,000 hectares (that’s 14,000 soccer fields) of pine forests near Descargamaría in May 2023 not only leave their mark on the landscape but also on the local economy and people’s minds. Local residents, many of them older people, had to be evacuated from the wildfire as it encroached on the village last year. Back in 2015, another large forest fire burned over 8,000 hectares of land and forced 1,500 people to evacuate their homes.

“Last year we had a fire that came from Las Hurdes into the Valle del Arrago, but the wind changed and thanks to that and the great work from the firefighters, we were able to extinguish it, but not before it burned thousands of hectares. The year before that there was one in Torre de Don Miguel, where they had to evacuate the village,” Luis Mariano Martín, former mayor of Villasbuenas de Gata and now the president of the local rural development association ADISGATA, tells REVOLVE outside his property in Sierra de Gata.

“This is the tune that plays out every day. It’s a never-ending fight, and when summer comes around, we’re all scared to death of what might happen,” he adds.

FANNING THE FLAMES

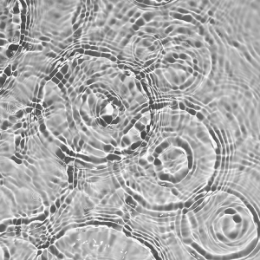

Climate change will make wildfires more intense as rising temperatures make landscapes and vegetation drier for longer periods of the year. There were 371 recorded fires in Spain in 2023, which burned a total of 91,220 hectares, according to the European Union’s fire monitoring satellite service EFFIS, which may also include intentional fires set for vegetation burning or agricultural purposes. The year before that there were 494 fires recorded, with a combined burned area of 306,555 hectares, the highest this century for Spain. Of those, 56 were considered large forest fires over 500 hectares.

Although it is hard to put an exact tally on the economic damage caused by a wildfire, the initial land restoration budget allocated by the Extremadura regional government for the May 2023 blaze, for example, was 15 million euros. A March 2023 report estimated annual losses caused by wildfires in regions of southern Europe to be between 13–21 billion euros. This is considerable in an area like the Sierra de Gata, where the unemployment rate sits at 12%, according to ADISGATA.

However, the core driver of intensifying forest fires in rural Spain is population decline. Between 2011 and 2021, the number of people living in the Sierra de Gata region decreased by nearly 11% from 23,056 to 20,570. People over 65 make up almost 30% of the population, well above the Spanish average of 19%. In Descargamaría, there are now only around 50 year-round residents (the census will tell you 103 due to others registering their legal address in the village), a far cry from the over 700 back in the 1960s according to the Spanish Statistical Office (INE).

There are wildfires because there is no local economy and there is land abandonment.

Fernando Pulido

When rural people pack up and leave the area, they take with them traditional jobs like livestock herding, farming, and tree cultivation, which once shaped the forests of the Sierra de Gata into a mosaic landscape. In their absence, vast expanses of pine trees have moved in, creating uninterrupted swathes of woodland and turning the region into a tinder box ripe for an out-of-control fire.

“There are wildfires because there is no local economy and there is land abandonment,” says Fernando Pulido, a professor of forest science and conservation at the University of Extremadura (UEX) and well-known face in the Sierra de Gata for his work on wildfire prevention. “There is a change in social dynamics as people leave here for the cities. This leaves us with a forest that is unmanaged, leading to overly large forest fires,” he adds in an interview with REVOLVE.

MOSAIC LANDSCAPES

As part of the RESIST Project, Pulido and local partners in the Sierra de Gata are working to implement strategies that not only mitigate the risk of wildfires but also offer economic opportunities that keep local communities in the area.

“We believe that we can turn wildfire prevention into an opportunity if we can approach it in a way that is participatory with local stakeholders,” Pulido says. “If we revive the sustainable economic management of the land, we will be making a positive contribution to wildfire prevention. It’s about tackling the root of the wildfires.”

One way this is being done is by creating professional networks between people already working on the land to amplify their impact on the forest. Another is being demonstrated with a case study that will clear 10 hectares of forest in a high-fire risk area – specifically, the area that burned in May 2023 – to set up a chestnut plantation. This pilot will be financed through the project, meaning no direct costs will be incurred by local associations.

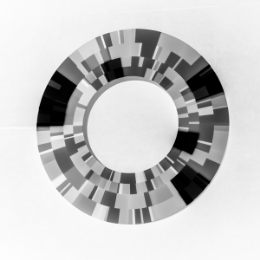

“If we generate discontinuities in the forest, something we call productive firebreaks, then we can stop the fire or at least ensure that it is smaller and less catastrophic,” Pulido says, providing examples of traditional activities like goat herding and tree cultivation, which both manage the expanses of forest by reducing tree density. Human or animal activity in between the trees also helps to keep the undergrowth and scrub down. Combined, these effects on the forest make it harder for flames to spread through the canopy and the forest floor.

There is nothing new about the mosaic system in the Sierra de Gata. In fact, it marks the return of a rural system that was once prevalent in the region. The trick is to make it economically viable.

TAPPING INTO RURAL TALENT

One person trying to do this is Javier Calzada, a Sierra de Gata native in his early 20s who has turned his hand to resin tapping, making use of the ample pine groves in the region. The resin he extracts is sold for multiple manufacturing uses, notably to make medical pill capsules.

“I started resin tapping because I like nature, I like to work outdoors, and most of all because I get to set my own rules,” he tells REVOLVE in an interview at his plot of Pinus pinaster pine trees.

Calzada explains that the resin in the trees is easier to extract when the temperatures rise above 27 C (80 F), which means most of the process takes place in the summer. But preparations begin as early as February, when he begins to make small cuts into the bark at the bottom of his trees, under which he places a funnel contraption and small black bucket to collect the resin.

A resin tapper is like a permanent watchperson in the forest because it’s not in their financial interest to have a fire burn their source of income.

Fernando Pulido

As a self-employed worker, he says that price fluctuations in the resin market and precarious finances can make the job challenging but acknowledges the existence of economic help from local authorities. By choosing to be a ‘resinero,’ Calzada is able to work near his hometown while at the same time returning a service to his local community when it comes to wildfire prevention.

“Resin tappers are an interesting case of productive firebreaks,” says Pulido. “If there are resin tappers, there are two benefits. Firstly, they move around and eliminate vegetation and shrubs. It is like there was a herd of goats in there. But most of all, the resin tapper is like a permanent watchperson in the forest because it’s not in their financial interest to have a fire burn their source of income. And it’s this double effect, of cleaning up vegetation and surveillance, that interests us about the resin tappers.”

KNOWLEDGE SHARED

The efforts to revive the local economy in the Sierra de Gata are generating knowledge that can be of use to other depopulating areas of rural Spain and farther afield. In early April, RESIST partners from Central Portugal and Extremadura took part in a two-day field visit between their respective regions, which border each other, to learn about some of the shared climate challenges being addressed in the project. Once validated, the solutions tested in these regions will be shared with others participating in the project across Europe.

But the impact of these solutions will be felt closer to home for the Sierra de Gata residents, many of whom are involved in the project activities as co-creators and beneficiaries. Equipping people with the tools and resources to make a living will ultimately shape the landscape in rural Spain.